GET doesn’t change the world

A Mendeley HTTP bug could trick visitors into adding papers unknowingly.

Recently, I wanted to offer my visitors the option to add any of my publications to their Mendeley paper library. When creating the “add to Mendeley” links, I noticed that papers got added without asking the visitor for a confirmation. Then I wondered: could I exploit this to trick people into adding something to their Mendeley library without their consent? Turns out I could, and here is why: Mendeley did not honor the safeness property of the HTTP GET method.

Safeness and idempotence provide guarantees

The HTTP specification defines for each HTTP method whether it satisfies these two important properties:

- safeness

- A method is safe if its invocation does not change resource state.

- idempotence

- A method is idempotent if multiple invocations result in the same as a single one.

For example, the GET method is defined as safe and idempotent: if you GET a page about a recent movie, you expect your browser to show information about the movie’s cast and plot, not to buy you a ticket (yet). And if you GET this page twice, you expect to see the same result again. This is unlike the POST method, which is unsafe and non-idempotent: performing a POST might actually buy a ticket. If you do it twice, you’ll have two tickets. Do it three times, and you’ll have tree tickets. Keep on repeating, and you’ll have the cinema hall all for yourself. So GET is safe, POST is not.

The correct implementation of the safeness and idempotence properties are essential to make HTTP clients (such as browsers) and devices (such as servers and caches) do their job. For example, a browser doesn’t warn you if you go through your history and want to reperform the GET request on the movie’s page. This behavior is justified because there’s no harm GET can possibly do: GET does not change resource state (safeness), and repeating a GET multiple times does not have a different effect than only issuing it once (idempotence). However, your browser will warn you if you try to reperform the POST request, since POST can do harm by changing the resource state and having a different result when executing the request multiple times (its unsafeness and non-idempotence might buy many tickets instead of just one).

Taking safe methods to a dinner

The safeness property is often explained in terms of “changing the world”. A GET request shouldn’t change the world, but a POST request can. However, what do we do for example with visitor statistics? Tools such as Google Analytics track when people visit pages, and most of these visits are GET requests. Other sites such as YouTube count how many people watched a video, which is also a GET operation. Or maybe the server performs actions internally as a result of GET request, such as caching and optimization. Are these cases violations of the HTTP protocol?

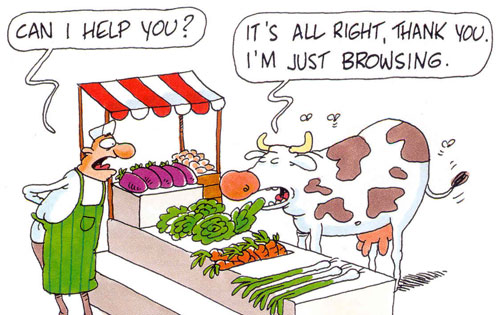

Strictly speaking, they are, but the server must not consider any safe action as a deliberate advance by the client. In other words, performing safe requests is like browsing the menu at a restaurant. Sure, the waiter can make suggestions if he notices you’re into rib eye steak, but he can’t pass the order to the kitchen just yet. That’s an obvious matter of politeness, and an implicit agreement—

Mendeley wasn’t playing safe

When this agreement between client and server is broken, undesired behavior might occur. Mendeley, an academic social network and digital paper library, had an interesting security bug as a result of not honoring the safeness property of GET. The URLs to add papers to Mendeley are constructed like this:

http://www.mendeley.com/import/?url=paper_urlFor example, to cite a paper from my website, this becomes:

http://www.mendeley.com/import/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fruben.verborgh.org%2Fpublications%2Fverborgh_wsrest_2012%2F

What I noticed is that, when I clicked the link above—GET request to that URL for me—

What’s worse is that I (or anybody else) could trick people that way into adding papers to Mendeley, without their consent. We just have to trick their browsers into performing a GET request, which is actually easy. For example, we could add images to our homepage that look like this:

<img href="http://www.mendeley.com/import/?url=paper_url">See what I did there? Here’s what would happen:

- A non-suspecting visitor decides she likes to visit our homepage.

- Her browser reads the

imgtag. - Her browser

GETs the “image” (which is actually a page). - The image doesn’t display (since it’s a page), but…

- As a result of the

GETrequest, Mendeley adds the paper to her collection!

Implementing a state-changing action as a GET operation is not just a formal mistake, it can have disturbing, undesired consequences for end users.

![[Profile picture of Ruben Verborgh]](/images/ruben.jpg)